The Stone Mill in Lawrence, MA

By Mark Fogarty

6 min read

A New Era Starting for Historic Massachusetts Mills

They built the great mills along the Merrimack River in Lowell and Lawrence, MA to last. And now many of these old symbols of Rust Belt America north of Boston are getting the rust chipped off to be rehabbed into sturdy housing for people of all incomes.

For instance, The Stone Mill, which the Boston-based WinnCompanies is developing to hold 86 units of all-electric, energy-efficient housing, “is in surprisingly great structural shape,” says Angela Gile, senior project director at WinnDevelopment, of a building that is more than 150 years old.

The mill’s slate roof “has held up really well,” meaning there was very little, if any, water damage below, which is not common for old mills. “It has good bones,” Gile says.

The building is the city of Lawrence’s oldest mill, built between 1846 and 1848 by Abbott Lawrence, the namesake of the city. “It was part of what ended up being a pretty big campus of mill buildings,” says Gile, “only it and two other mills remain from the original campus in the East Canal area of Lawrence.”

WinnDevelopment Executive Vice President Adam Stein says the mill will be converted to “a building that will use 40 percent less energy and emit approximately 30 percent fewer greenhouse gases than a new gas-heated building.”

Originally the building was called the Essex Company Machine Shop. Industrial uses for the mill back in the day included textiles, parts for steam locomotives and parts for the other mills in the area.

The Lawrence Mills have had a place in labor history since the famous “Bread and Roses” strike was called there in 1912, and photographs by photographer Lewis Hine let the country learn of the child labor that was going on in the mills.

After the industrial operation ceased, the mill may or may not have sat empty for a time and then had various commercial uses, a hodgepodge that includes office space, a children’s theater, an antique mall, among other uses.

Winn purchased the property in August 2021, Gile says, and made plans to convert it to mixed-income apartments. Construction on the one-, two- and three-bedroom units began in June 2022 and is expected to be finished sometime in 2024.

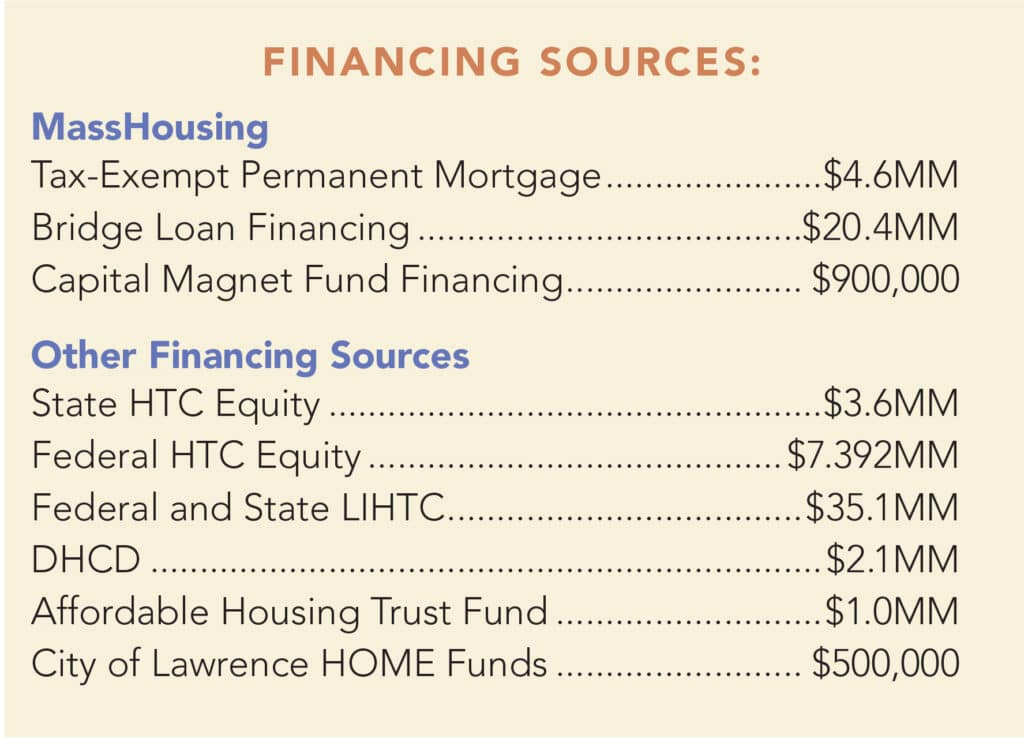

Affordability will range from 30 percent of area median income (AMI) to market-rate units. The project has been granted both State and Federal Historic Tax Credits, as well as State and Federal Low Income Housing Tax Credits. The total development cost is $50.5 million.

A Mix of Units

Plans call for 58 units to be available to those at 60 percent AMI and below, 11 to residents at 30 percent and below and 17 at market rate.

Winn got its start rehabbing mills in 2005 with one called Boott Mills, a massive, 188-year-old brick complex along the historic canal system in nearby Lowell, which is upstream on the Merrimack River. Although the company has developed award-winning new construction, and mixed-income housing properties throughout the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states, its successful track record in the adaptive reuse of 42 historic properties tend to draw the most attention.

The Stone Mill in Lawrence is within walking distance of a commuter rail for residents who will work in Boston and is accessible by highways and freeways, she says.

The historic detailing of the rehab extends to the inside of the buildings, as well as the outside, she says.

“That might look like exposed brick walls in select areas of common areas and units or exposed beams,” she says. “At The Stone Mill, there are large pieces of equipment, an old water turbine from when the mill was powered by water, and we’re leaving all that in place and having it be accessible and viewable to anyone coming in the front door.”

The total impact of old and new industrial gives off “a pretty attractive vibe,” Gile says.

Gile says Winn’s practice of rehabbing old mill buildings in Lawrence and Lowell (and in other places as well) has generated years of experience in how to evaluate the old buildings and assess future use.

“We’ve done a lot of these mills with the same excellent team of architects, engineers and general contractors. Winn also knows how to put the financing together, not just the LIHTC program but the state and federal historic programs, making sure the building is appropriately registered, working with consultants to make sure it is meeting all the historic building requirements,” says Gile.

“The mills tend to be some of the most interesting and exciting projects because they tend to be in areas of these cities that are great areas, like downtown, close to transit, close to amenities, the waterfront. They may have been sitting there, underutilized or not being utilized at all, for a long period of time,” she says.

“It’s always great to come in with a team to reposition the assets. They complete many goals, and we think the buildings, mills especially, convert into units of great housing for people. You tend to have larger units with huge windows and desirable features you may not even get in a new construction building.”

The same thing tends to be true of Winn’s old-school conversions, she says.

No More Fossil Fuels

The Stone Mill will no longer need the adjacent Merrimack River for a power source as it did a century ago, nor will it be using fossil fuels. The all-electric energy-efficient conversion of the building started off with a bang, literally.

A natural gas pipe explosion rocked the adjacent area. Lawsuits then brought in money being used to support these kinds of energy conversions. In general, municipalities and states are moving toward not allowing gas hookups for new construction, and things like building codes are increasingly encouraging or requiring all-electric buildings.

“Our Winn in-house consultants focus on how to make our projects sustainable and energy efficient,” says Gile. The resulting plans called for all-electric, highly-performing buildings.

“We typically do mill rehab buildings to a strict standard when it comes to energy efficiency, but The Stone Mill is above and beyond anything we’ve done before.” It has access to $2.88 million in gas explosion money from the Merrimack Valley Relief Funds—these funds are to be used only for the geography to support all-electric buildings and are not widely available—from the Department of Energy Resources to work with to support aggressive energy efficiency goals and have no natural gas hookups. For example, “instead of the standard typical dual pane windows, we’re doing triple pane efficiency windows. And instead of the typical two to four inches of wall insulation, we’re doing six inches of exterior wall insulation,” says Gile. Construction and design elements like this will result in an efficient, and comfortable building to live in, that does not rely at all on fossil fuels.

This is Winn’s first all-electric mill, and Gile says the idea is to construct a roadmap for doing more of them going forward.

MassHousing, which is involved in the project, says it has closed on $25.8 million in financing for The Stone Mill, which it says will be the first all-electric housing development in Massachusetts.